Updated July 2023

Sylvia Spalding brings a unique background to Climate Land Leaders. A long-time resident of Honolulu, she spent a career in fisheries management in the Pacific Islands and today is bringing insights from that career to her stewardship of family land in Mahaska County, Iowa.

Her family’s history in Mahaska dates back to 1837, when her ancestors began claiming land as white settlers even before the New Purchase — the cession of Native American lands in central Iowa to the United States in 1843. The family’s final land acquisition was made by her grandfather in 1943.

Sylvia’s father joined the military service during the Korean War and met her mother in Japan, where Sylvia and her two older siblings were born. Her family returned briefly to “the home place,” as Sylvia calls it, in Iowa when she was 2. However, early the next year, her parents and their young family returned to military life, due to the culmination of a farm accident, lack of substantial income, and the isolation of rural life for an ESL emigrant with young children, not to mention the anti-Japanese sentiment of rural America in the shadow of World War II.

During family visits to Iowa, Sylvia picked up a love for the family farm – she recalls drawing pictures of the farm and getting upset when told she “had to stay home with the womenfolk.” She wasn’t allowed to go hunting, but she did get to fish, an interest that developed into a fisheries management career after her family settled in Hawai’i.

Sylvia has been managing her family’s multi-generational farm on the South Skunk River for the last 17 years and travels 2-3 times a year from Hawai’i to Iowa to work on more significant projects. Today the 117 acres include 54 acres of former cropland enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) and 49 acres of woodland certified as a manged American Tree Farm. Sylvia’s goals for working with the land are comprehensive and holistic, spanning land and water management, family and community relationship-building, and planning for the eventual transition of the land to new stewards. She developed her goals through a land school offered by Ecological Design which was founded by another Climate Land Leader, Paula Westmoreland.

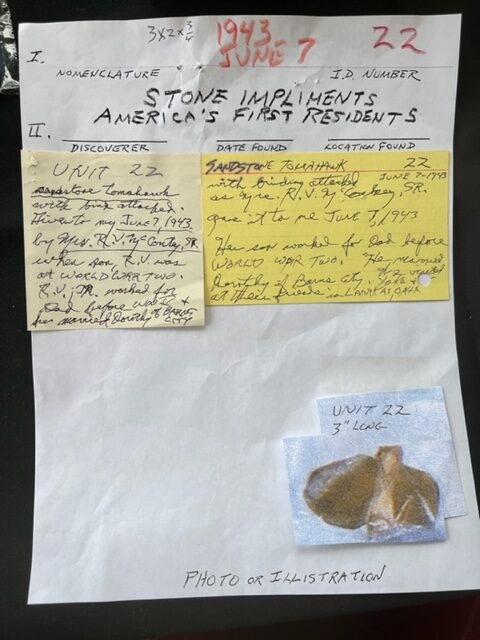

The land is the ancestral homeland of the Oneota, Baxoje (Ioway) and Meskwaki (Sac and Fox) peoples. Another goal Sylvia has is to promote greater recognition of former Native American presence on what are now Iowa farmlands. Her father has passed onto her artifacts and maps that he drew as a young person documenting where he believed there were villages, battle areas, lookout areas and burial grounds. “The thing about having land in the family is you have all these places with stories,” Sylvia shared, drawing a parallel to the role of intergenerational knowledge in the Pacific Islands.

Sylvia is also pursuing a cultural argument against the proposed Navigator carbon-dioxide pipeline poised to cross 36 counties in Iowa, paralleling the Dakota Access pipeline. Sylvia first connected with other Climate Land Leaders through individuals she met while working with the Bakken (Dakota Access) Pipeline Resistance Coalition, and she continues to organize in her community to bring more transparency, public input and accountability to the Navigator process.

Sylvia understands just how ingrained our current, extractive energy system is, including the long history going back several generations of landowners signing land easements based on eminent domain. She recalls her own family’s perspective: “My grandmother thought we might as well get what we can, because they’re going to take it anyway – that’s the mentality.” Sylvia’s perspective? “When are we going to get off the oil and use more energy efficient technology and natural carbon sequestration instead of these CO2 sequestration lines that perpetuate the fossil fuel industry?” she asks, and points out that “companies are making huge profits off of property that get a one-time payment.”

“Sometimes when I’m in Iowa and I’m half Japanese and the township is 99% white, I can feel a little displaced,” Sylvia shares. But, she says, “there’s a lot of input that can come in from Hawai’i,” particularly as the climate continues to change. Sylvia contrasts the climate change denial she still encounters in the Midwest to her experience in Hawai’i: “In the Pacific Islands, we’re little islands in the ocean, so we see changes more. We see the sea level rise. And working with fisheries, the acidification of the ocean, which is hurting the calcification of shellfish and the embryos of fish – that’s going to be major damage… We see the migration of the fish moving north, and we’re starting to see this on the land, too, where species are starting to move up to higher latitudes as aquatic species are moving to lower depths.”

Sylvia retired from roles as a board member of Hawai’i Interfaith Power and Light and more recently as co-chair of the National Marine Educators Association’s Traditional Knowledge Committee and acting executive officer of the International Pacific Marine Educators Network, two groups she helped form in 2007. She also helped organize two symposia at the Smithsonian National Museum of American Indians on climate impacts on coastal indigenous communities, the first-ever indigenous group to the Ocean Observation decennial conference, the NOAA Fisheries inaugural climate science regional action plan for the Pacific Islands, a video on the impacts of climate change on small island communities, and climate education for students, teachers and communities. Much of her work has focused on the bringing together of Indigenous knowledge and Western science through ‘two eyed seeing’ – through the two lenses of an Indigenous way of observing and a Western way of observing. “They don’t need to be integrated,” Sylvia says, “but we need to acknowledge and honor both. Traditional knowledge is a holistic way of viewing the world, so [in the case of marine education and resource management] you can’t subsume it under the ocean only.”

As she reflects on the critical role of the watershed in her Iowa community, Sylvia brings in another Indigenous concept – ahupua‘a in the Hawaiian language. Sometimes likened to ‘watershed,’ ahupua’a is a traditional Hawaiian land division “typically from mountain to ocean, encompassing the people who live in the area and all of the resources the community needs to live in the area.” She also describes ways of working together to steward resources that are less regulation-based and more education- and code of conduct-based, drawing on her work with Indigenous practitioners of fishing and agriculture.

Sylvia is eager to connect with more neighbors and extended family in the farm’s community, and she looks forward to welcoming more people onto the land and inviting conversations about shared stewardship. “I would like to incorporate the ahupua‘a concept, this broader understanding of ‘watershed,’ as I’m looking at building community in Iowa – ‘Hey neighbors, we have all these streams together…’”