Climate Land Leaders frequently come together to learn from each other and from experts in climate-friendly agriculture. Jack Hedin of Featherstone Farm is both a Climate Land Leader and veteran vegetable farmer in southeast Minnesota, and he recently joined the group for an illuminating conversation about growing commercial vegetables as the climate changes. Here we’ll share three misconceptions, one persistent challenge and a key advantage Featherstone Farm has cultivated to continue growing food and sustaining a viable business in a destabilized climate.

First, to give you a sense of place and scale: Featherstone Farm has operated for over 25 years in southeastern Minnesota in and around Rushford. They grow about 145 acres of certified organic vegetables, which looks like 4-5 semi trailers of fresh market produce going out weekly to their CSA [Community Supported Agriculture], grocery and wholesale customers. At peak season, the team is around 50 workers, many of them long-tenured at Featherstone.

Misconception #1: The proliferation of farmers markets, small producers, CSAs and other farm-to-table options means that this must be a financially viable, flourishing industry. While there are financially viable operations within these categories – and smaller scale operations serve critical roles within our regional food systems – the reality is there is a significant gap of commercial scale farms like Featherstone operating in Minnesota. It has taken Featherstone years of growing to its current scale to be long-term viable, including being able to provide employee retirement benefits. Given the level of risk-taking, capital and labor investment, and how critical fresh fruits and vegetables are to community health, Jack believes the odds of long-term viability should be better.

Misconception #2: “The growing part” of operating a vegetable farm is straightforward. Honing the business model while growing into markets and scaling operationally are critical activities that hold plenty of challenges, from Jack’s perspective. Running a commercial-scale farm, especially in a destabilized climate, is far more difficult than growing backyard gardens.

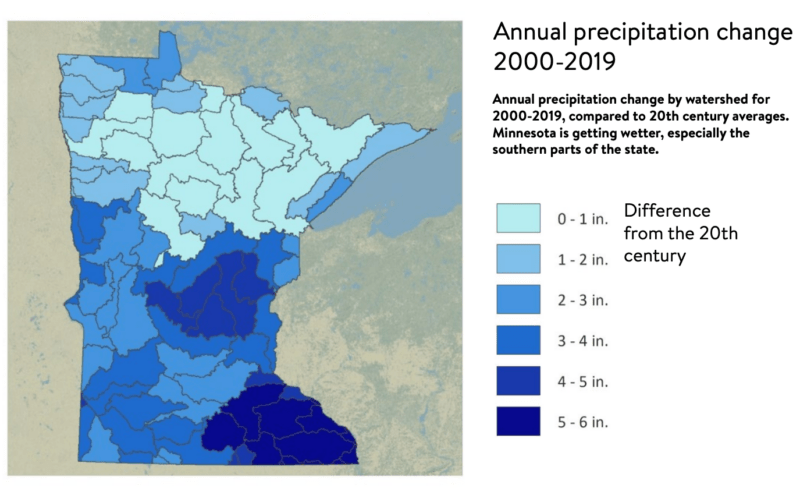

Misconception #3: Farmers like rain. There’s a reason the U.S. commercial produce industry is centralized in the arid West. “Rain in the Midwest is always a problem for what we do,” Jack shared. Plants are more likely to get sick when it gets wet. Jack described the more recent challenge of “chronic wet periods” – 4-5 days with high moisture and dew points and a lack of conditions that in past decades would dry out soils and foliage and reduce the risk of disease.

One persistent challenge, exacerbated by climate change: the market rewards low prices and consistency. Consumers want beautiful, predictably available, cheap produce – which are very difficult to grow, especially with Midwest weather patterns. At its scale, Featherstone competes for grocery and wholesale customers with California producers, who grow in very consistent weather conditions (even as the California system is threatened by chronic drought). In Rushford, Featherstone has adapted to increased rainfall, chronic wet periods and huge swings in overnight temperatures by growing lower volumes of volatile crops that have narrow harvest and storage windows – crops like tomatoes, melons, and broccoli – and growing higher volumes of crops like carrots and other root vegetables that have a wider harvest window and long storage window. Featherstone is also adding more high tunnels, although this represents a significant investment at their scale, and using more horticulture plastic as ground mulch to mitigate against wet conditions.

From Jack’s perspective, “Disease is the greatest risk where we live.” But Featherstone has a key advantage – what Jack calls its “A+ farmland,” with soil fertility, microchemistry and microbiology cultivated over years of organic management and soil-building crop rotation contributing to plant vitality and draining excess moisture. “Soil is the greatest buffer and protection against disease,” he says.

— Thank you to Sarah Hunt, Climate Land Leader from St. Paul, MN, who wrote this blog post.