Mary Swander’s new play, “Squatters on Red Earth” premieres this weekend—and Climate Land Leaders will be there to experience this performance that includes a tale of cooperation and also one of land theft. The play opens June 9, 8 pm at the Amana Performing Arts Center, Amana, Iowa, and June 10 at 2 and 7 pm, The Wieting Theatre, Toledo, Iowa. Here are some excerpts from Mary’s podcast about the play.

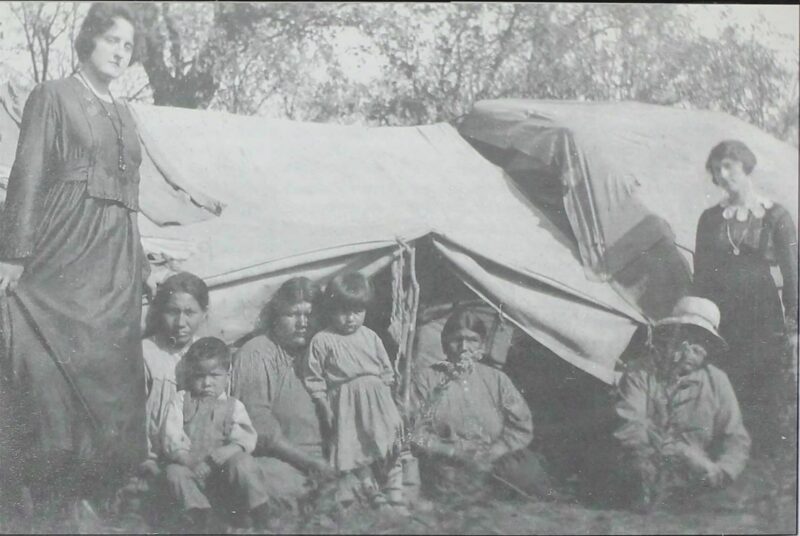

“… The play centers on a peaceful relationship between the Amana Inspirationists and the Meskwaki Native Americans during the white settler land grab in the United States. Annuities, treaties, allotments, and Indian Removal Acts were all designed to drive the Natives from their land and develop agriculture, towns, cities, roads, railroads and industry across the vast western expanses of the United States. The white settlers convinced themselves of the righteousness of their actions, in part, through their belief in ‘Manifest Destiny,’ the idea that they were destined by God to ‘tame’ the Western land and its people. They thought they were ordained to dominate the space and create a prosperous society.

“I knew the broad brushstrokes of that history, although I didn’t realize how calculated the land grab actually was. In my own mother’s family–white settler famine Irish– the story was a bit different. We were Irish homesteaders–colonialists fleeing British colonialists–who plopped down in western Iowa on Native land. There, my great-grandparents raised a family of ten, losing several infants, but living side-by-side for years with the Natives–most likely the Pottawattamies.

“My great-grandfather built a house, a duplex of sorts. My family lived peacefully on one side and Natives lived on the other. The Natives had the good sense to leave Iowa in the winter for the South, but they returned each year to live temporarily in their wigwams.

“’We always knew it was spring,’ my grandmother told me, ‘when we looked outside and saw the Natives putting up their wigwams in the pasture.’

“I imagined that there had to be other cooperative stories like this, clearly different from the standard textbook history I’d been fed as a child. We were still talking capitalism and colonialism, but with faces on the people involved. My mother’s family was pushed out of their homeland by the potato famine, a result of British imperialism. Then they came to the States and pushed another group off their land. Did this kind of displacement repeat itself throughout history? And what was the land on the plains like when my family arrived? The Natives were hunters and gatherers, but did they farm? If so, what were their techniques?

“A few winters ago, I plopped down in my chair in front of my woodstove and dove into a pile of books, from the history of the settlement of Turtle Island, to the ideologies of those who came for plunder or adventure, to those fleeing war or religious persecution. I read about the natural history of the Midwest, the great expanses of prairie, the wetlands and savannas.

“The Europeans looked at the Midwestern landscape as nothing more than a bunch of weeds. But underneath the weeds, they discovered rich, black soil, soil that could grow an abundance of food. So, they drained the wetlands, plowed and planted without thought of losing this precious topsoil through erosion or mismanagement. They shot bison out of train windows for sport, fenced the land, and grazed cattle.

“In contrast, I read about the Natives and their ecological and sophisticated agricultural systems of agriculture, from the ways they harvested game, to the ways they created complex irrigation systems in the desert, to their floating gardens in the middle of lakes in Mexico. Bison were a key component of prairie ecology, providing food, clothing, and shelter for the natives. The bison grazed the grassland, preventing trees from taking over the prairie. The bison hooves pushed the prairie seed into the soil, allowing grasses and wildflowers to thrive.

“Today, we’re ‘discovering’ techniques like no-till farming, companion planting and prairie strips that Natives were implementing thousands of years ago.…

“Finally, I knew I couldn’t begin to write the play without the help and guidance of Native Americans, so I contacted my former student and friend Shelley Buffalo at the Meskawki Settlement in central Iowa. She arranged a meeting with a group of Meskawkis who provided me with historical background, oral histories, their perspective on the issue, and advice about composing and producing the play.

“’We don’t want genocide on the stage,’ Suzanne Buffalo said. ‘It’s too triggering to our youth.’

“I agreed.

“’How about dramatizing our relationship with the Amana Colonies,’ Shelley offered, filling me in on the story. The Meskwaki had originally lived on the land the Amana Inspirationists settled, planting lotus in the wetland that would become known as The Lily Lake. Then the Federal government drove the Meskwakis off their land to a reservation in Kansas. They longed to return to Iowa, but knew nothing of money or land transactions. The Inspirationists bought back the Meskwakis’ own land, then held the deed until the Natives could pay them back by selling furs and other goods.…

Mary Swander’s play is quite a collaboration, including: Set designer Shelley Buffalo, Director Brant Bollman, actor Rip Russell, puppeteer students from the Meskwaki Settlement Middle School, singer and composer Laura Hudson Kittrell, Historians Mary Bennet and Peter Hoehnle, costume designer Michele Payne Hinz and more.

Funders include: Anonymous Was a Woman in cooperation with The New York Foundation for the Arts, The State of Iowa Historical Society, Inc. and an anonymous donation. These performances are free and open to the public with a suggested free-will donation. Tickets–first come, first serve–at the door. Or, to reserve free tickets, put “Tickets” in the subject line and email agartsoffice@gmail.com. Funders include: Anonymous Was a Woman in cooperation with The New York Foundation for the Arts, The State of Iowa Historical Society, Inc. and an anonymous donation.